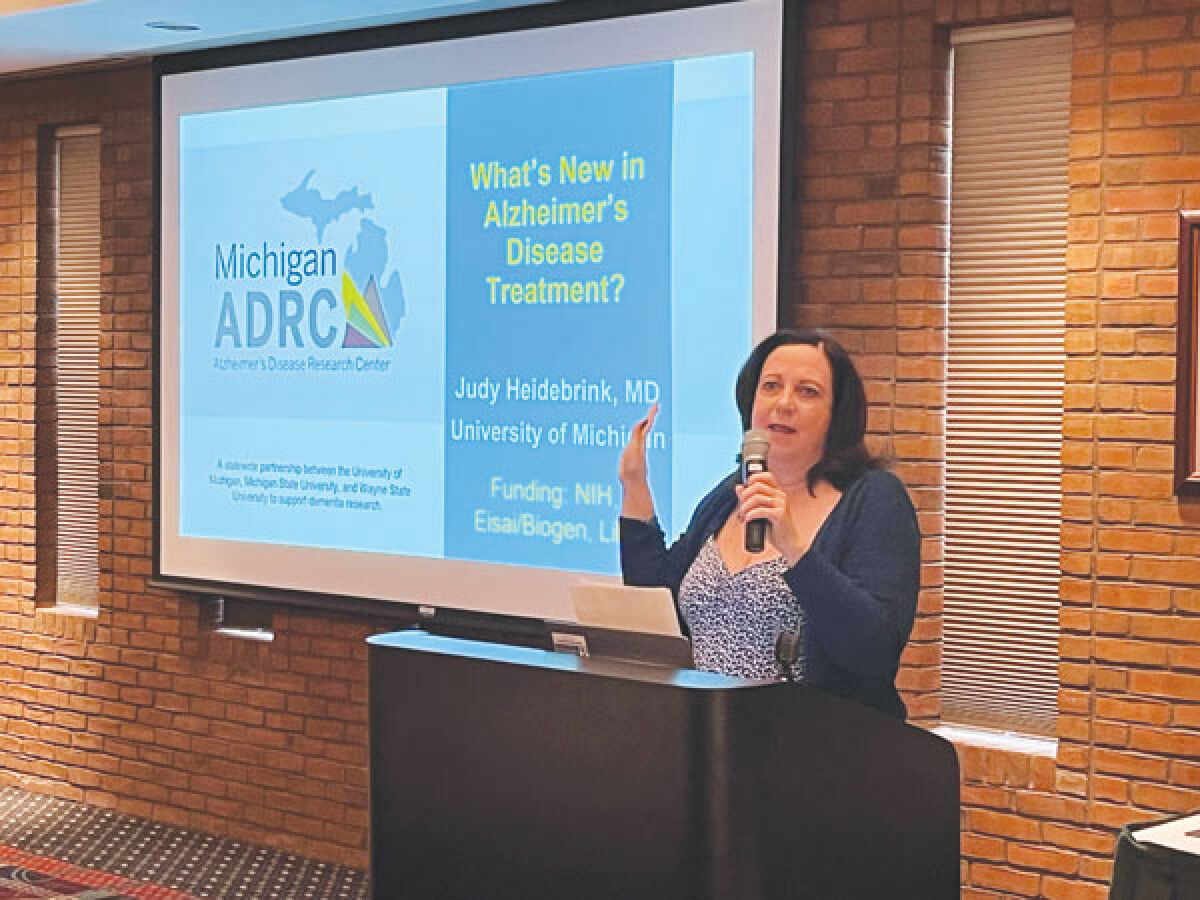

Dr. Judy Heidebrink, a professor of neurology at the University of Michigan, gave a presentation regarding advancements in Alzheimer’s disease research in Troy.

Photo by Brendan Losinski

TROY — At a presentation at the Michigan State University Management Education Center in Troy May 16, the Michigan chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association said that exciting new advances in Alzheimer’s disease research are in development.

The keynote speaker was Dr. Judy Heidebrink, a professor of neurology at the University of Michigan and a member of the Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, which is housed at the University of Michigan but is a collaboration of the University of Michigan, Michigan State University and Wayne State University.

“I’m trying to share the excitement we have about some new therapies that are disease-modifying, meaning they don’t treat symptoms but actually target the direct pathology of Alzheimer’s disease and can make a direct impact in slowing the progression of symptoms,” Heidebrink said.

Jennifer Lepard is the president of the Michigan chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association and hosted the event.

“These advancements are amazingly significant,” remarked Lepard. “I’ve been working for the Alzheimer’s Association for 10 years, and up until now we have only had drugs that treated symptoms. Nothing has ever slowed the decline (resulting from) the condition before. With what is in the pipeline, it seems like there is even better news on the horizon.”

Heidebrink said that two new therapies are currently being tested, Aducanumab and Lecanemab. Both target the amyloid proteins involved in Alzheimer’s disease and are in the process of approval by the FDA.

“The newest therapies are anti-amyloid antibodies, which are antibodies directed against the amyloid protein, which is the main component of the plaques that build up in the brain when someone has Alzheimer’s disease. They exist in an intravenous form, so they are not a pill that you take. It’s an infusion that you get. There is solid data showing that individuals that have symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and have amyloid plaque buildup will see a reduction in that buildup of that plaque with these treatments over time,” she explained. “What was most encouraging recently was that when the amyloid buildup was reduced, progression of the symptoms also decreased.”

She added that these are the first major steps in Alzheimer’s research since the early 2000s, but there is some concern that rare patients might have hemorrhaging or swelling in the brain as a side effect, so more research into them is being conducted.

Despite the challenges, Lepard said that those in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease are excited about what these steps could mean.

“There are new treatments on the horizon, and they are the first treatments that are treating the underlying causes of the disease,” she said. “In order to benefit from these treatments, you need to get a diagnosis and you need to talk to your doctor, so we also are encouraging the public to get that diagnosis. Some symptoms can be something other than dementia and can be treatable, and some people write it off because they think there’s nothing that can be done.”

Lepard said her organization hopes to inform more people about these new advancements.

“We used to do events like this a lot before COVID. During COVID, we did some virtual events,” she said. “We’re so happy to be back in person. Basically, we do about six across the state a year. We have three this year. We just invite the public in to hear what is going on and what the new developments are in Alzheimer’s research.”

One of the major reasons the Michigan chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association hosts these meetings is to remind people that Alzheimer’s is not a hopeless condition and that people can and should speak to their physicians about it.

“Sometimes there’s misconceptions and people think there’s no point in knowing if someone has Alzheimer’s because there’s nothing that can be done,” said Heidebrink. “I want people to know that there are therapies that can be effective and might be a foot in the door to even better therapies in the future, so I am hoping events like this will encourage people to talk to their clinicians about whether they are candidates for such treatments or trials.”

“It’s not hopeless,” Lepard added. “Even if all these drugs can do is slow the progression, that is more time to live the life you want to be living.”

Those looking for more information can go to www.alz.org/gmc or call the Alzheimer’s Association’s free number at (800) 272-3900 to ask for advice or information about support groups or local resources.

Lepard’s father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s five years ago, and she said the emotional toll of that cannot be underestimated.

“Alzheimer’s disease affects one in three people by age 85,” she said. “We know people are living longer. This disease can affect anybody. There is no hereditary factor. The saying we have is ‘the biggest risk factor for Alzheimer’s is aging’ and because we are beating other conditions, people are living longer. It affects not just the one with the disease, but it affects the family and it affects them physically, financially and emotionally.”

Heidebrink believes that the next 10 years could be a groundbreaking time for Alzheimer’s research.

“On the scale from ‘no progress’ to ‘a cure,’ these treatments fall roughly in the middle,” she said. “These drugs don’t reverse symptoms and they don’t cure people, but they are making progress and are showing that we can intervene biologically and change the course of someone’s progression over time. … I think we’re at the tip of the iceberg with some of these newer therapies.”

Publication select ▼

Publication select ▼