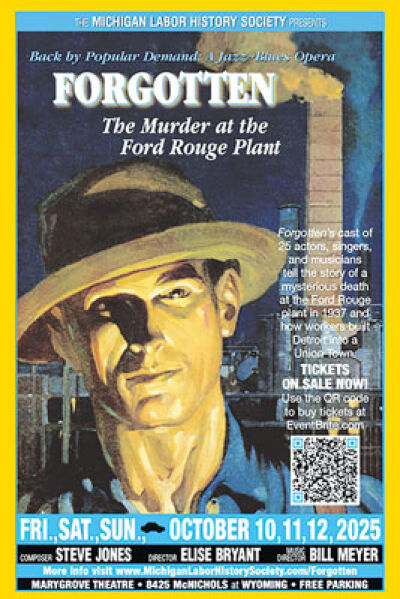

The poster for “Forgotten” was designed by Holly Syrrakos — the sister-in-law of the show’s composer, Steve Jones — and features a 1930s painting of an unknown worker by an artist with the last name of DeLappe.

Photo provided by Dave Elsila

Lucia Wylie-Eggert and Ben Blondy rehearse a scene from “Forgotten,” in which they portray Lewis Bradford and his wife, Ella.

DETROIT — Truth has a way of rising to the surface — even when it’s buried by years of fear and misunderstanding.

When the Rev. Lewis Bradford was found critically hurt in an isolated part of the Ford Motor Co. River Rouge plant in Dearborn in November 1937 and died days later, the incident was quickly written off as an accident. But Bradford, an advocate for working people and the poor, had drawn the ire of Henry Ford by broaching the topic of improving relations between workers and management.

While the family long suspected Bradford was the victim of foul play, it was only decades later that a relative who had never even met him uncovered the truth. In 2001, Bradford’s great-nephew, composer and musician Steve Jones, now 71, visited Detroit from Maryland. He managed to get a copy of Bradford’s 1937 autopsy report, and Carl Schmidt, the Wayne County coroner Jones spoke with about the report, confirmed that Bradford’s death should have been classified as a homicide.

Jones — who fleshed out Bradford’s life story through extensive research and interviews with relatives — has made sure that his great-uncle’s legacy and contributions to the labor movement are no longer lost. His jazz-blues opera, “Forgotten: The Murder at the Ford Rouge Plant,” recounts Bradford’s story, along with the Ford Hunger March, the Flint sit-down strike and the Battle of the Overpass — all important milestones in the effort by workers like Bradford to unionize.

“It was a remarkable story,” Jones said. “I got obsessed by it.”

A new production of the show returns to the place where it all started this month. “Forgotten” will be staged at 8 p.m. Oct. 10 and 11 and at 3 p.m. Oct. 12 at the Marygrove Conservancy Theatre, on the campus of the former Marygrove College in Detroit.

Bradford and his wife, Ella, had moved to Detroit in the 1930s to get medical treatment for their young daughter, Ella, who was suffering from a serious health problem. Lewis Bradford was an assistant to the pastor at Detroit’s Central Methodist Church and took a job at the Rouge plant because he needed to make more money to cover his daughter’s treatments. Having previously worked with unemployed and homeless people at the Howard Street Mission in Detroit, Bradford began to interview them on the air for a WXYZ-AM radio show, “The Forgotten Man’s Hour.” The show made Bradford a well-known figure in the community and stood in stark contrast to a national radio program on WJR-AM hosted by Catholic priest Father Charles Coughlin, who generated controversy by broadcasting anti-Semitic and pro-fascist sentiments.

After Bradford’s death at only 51, Jones said the coroner at the time told Bradford’s widow that she and her children could be next and they should leave town immediately.

“They were told not to talk about it,” Jones said.

The family promptly packed up and headed to Madison, Wisconsin. No one dared to demand an accounting of what had really happened.

“People were afraid to speak up,” Jones said. “It was not an easy time.”

Jones had trouble finding information about his great-uncle, aside from obituaries in papers across the country where Bradford had served as a minister. At the time of his death, the father of four had two children in college, along with a 13-year-old and a 17-year-old. Among the people Jones consulted was his aunt, who died a year and a half ago at the age of 105. She had been close to Bradford’s widow.

Bradford was a doting dad who would pull his kids out of school on a nice day to hike and enjoy the outdoors.

“He was kind of a whimsical guy who loved his kids,” Jones said.

His widow never remarried and kept a photo of her husband on her desk until the day she died, Jones said.

“I feel very relieved it’s no longer a secret,” Jones said of his great-uncle’s story. “I feel so good that this forgotten story could be told. I was told it would get shut down in Detroit, but as it turns out, people were curious (and wanted to see it). … The best honoring I could do was to write this show.”

Bradford was never able to definitively identify who killed Bradford, but the family strongly believes he died at the hands of one of Henry Ford’s internal security agents, who famously attacked United Auto Workers during the Battle of the Overpass — an incident that occurred just six months before Bradford’s death.

The show premiered in 2004 and was revived in 2005 and 2010 in metro Detroit, attracting sellout crowds. This marks the first time in 15 years that metro Detroiters will have a chance to see it. Jones said about 14 relatives of Bradford will be in Detroit to see the show as well.

“Forgotten” has also been performed in whole or in part in other cities, including New York, Chicago and Minneapolis.

This production is sponsored by the Michigan Labor History Society. Dave Elsila, of Grosse Pointe Park, is the show’s executive producer and a board member of the Michigan Labor History Society.

“People have kept telling us over the years, you’ve got to bring it back,” Elsila said.

The crew and cast of more than 20 includes many metro Detroiters. James Jacobs, of Grosse Pointe Park, and Laurie Stuart, of Grosse Pointe Farms, are on the production committee and John Dick, of Royal Oak, is a co-producer. Radio host and opera singer Davis Gloff, of Pleasant Ridge, plays Father Coughlin; Lucia Wylie-Eggert, of Farmington Hills, plays Ella Bradford; Kristin Ann Cotts, of Troy, plays Clara Ford; Linda Rabin Hammell, of Lathrup Village, plays a nurse assistant; and Kiesha Key, of West Bloomfield, is a member of the workers’ chorus.

Elsila said the show is engaging and entertaining as well as being enlightening, noting that they have “a really good cast” and live band.

“Steve’s a really great musician and composer,” Elsila said. “He has written 25 really wonderful songs. They are so catchy and so evocative.”

To enable more youths to see the show, Elsila said the dress rehearsal at 8 p.m. Oct. 9 is free for high school students.

“I think this is an opportunity for younger people to learn what their parents, grandparents and great-grandparents went through during the Great Depression,” Elsila said. “This is a story of love and hope and solidarity. They can learn a lot about Detroit labor history, Detroit history.”

Marygrove is located at 8425 W. McNichols Road in Detroit. Tickets cost $35. For tickets or more information about the show, visit MichiganLaborHistorySociety.com.

Publication select ▼

Publication select ▼